The broad landscape of philanthropy contains a vineyard of charitable needs and charitable gifts that weave together for the purpose of providing goodwill to the human race. Within that landscape is found the field of Catholic philanthropy, where those who plant the seeds support those who work the ground in order to grow the kingdom of God.

Charitable organizations of all sizes often focus their fundraising efforts primarily on gifts from individual donors, rather than working to build a relationship with a grant-making funder. From a purely financial perspective, data supports this strategy. In 2019, 79% of all charitable giving was attributed to giving by individuals and giving by bequests, according to Giving USA., compared to 17% from foundations and 5% from corporations.

The Bountiful Resources of Grantmakers

What many nonprofit organizations may not have considered are the benefits of cultivating relationships with grant-making organizations which extend beyond the financial support. Foundations often serve as topical experts and strive to share knowledge and research on best practices. If a foundation is not able to respond favorably to a funding request, it may offer to connect the organization with their network of other potential funders. Many foundations also offer training and development opportunities to build capacity and strengthen the vitality of nonprofit organizations.

Foundations may also serve as a connection to individual donors through donor-advised funds. For example, Meg Payne Nelson, Vice President of Impact for the Catholic Community Foundation of Minnesota shared that the foundation sponsors “Giving Insights Forums” focusing on social, spiritual and educational themes for their donors. Nonprofit organizations, representing some of the foundation’s grantees and some that may be prospective grantees, are invited to share their stories of impact with the donors, along with the data and anecdotal evidence that explains the social problem they are addressing. The events provide an opportunity for nonprofits to promote their services and highlight their impact as well as connect with potential donors for support of their programs.

For Catholic organizations, the benefits of working with a Catholic grant-making organization include a spiritual component of stewardship and shared mission. Those who work in service of Catholic nonprofits and grant-makers often recognize the opportunity for fulfilling the call to stewardship through their work, which compels them to give generously of their time, talents and treasure.

“Indeed, if we raise funds for the creation of a community of love, we are helping God build the Kingdom.”

– Henri Nouwen

“I would not be doing this work without my Catholic faith,” shared Joe Womac, President of the Specialty Family Foundation. “I look to the example of Christ to help inform all of my decisions. Our Catholic lens allows us to place mission first – ahead of the money.”

In their Pastoral Letter on Stewardship, the U.S. Bishops state: “As Christian stewards, we receive God’s gifts gratefully, cultivate them responsibly, share them lovingly in justice with others, and return them with increase to the Lord.” This mission to serve others through the example of Christ has motivated Catholic ministries throughout history.

Seeds of Growth: The History of Catholic Ministries

“…when we give ourselves to planting and nurturing love here on earth, our efforts will reach out beyond our own chronological existence.”

– Henri Nouwen

Catholic ministries and organizations have been vital to American society for centuries, with most of them founded directly by church leaders or religious orders. The earliest Catholic missionaries arrived in America shortly after the first settlers to spread the Catholic faith in the “new world.” Soon after, members of various religious orders began to establish schools in regions of the developing nation. The increasing numbers of Catholic immigrants to the U.S. in the mid-19th century led to increasing numbers of Catholic churches, schools and social service organizations.

Saving Souls in the 19th Century

The development of teaching, healing and social ministries was tied to the Catholic theology rooted in the Gospel message of Matthew 25 – “Whatsoever you did to the least of my brothers, you did to me” which compelled Catholics to care for the poor and sick as they would care for Jesus himself. Just as the broad definition of “catholic” infers “comprehensive,” or “universal,” the mission of the Catholic church “tended to focus on saving groups or categories of people within their social context, rather than approaching individuals singly” as was the practice of their Protestant counterparts. As explained in the report “Maintaining Vital Connections Between Faith Communities and their Nonprofits” the early Catholic ministries were formed primarily to provide pastoral care for Catholic immigrants and convert others to their faith. As a contributor to the report, Patricia Wittberg, a Sister of Charity of Cincinnati, wrote:

“Catholic hospitals were originally intended to foster repentance, penance for one’s sins through acceptance of one’s sufferings, and preparation for ‘a good death.’ Only secondarily were hospitals intended actually to heal anyone – the state of medicine was too primitive for that. Education was primarily to train the young in religious knowledge and good spiritual practices – only secondarily to teach secular subjects. Finally, social work was engaged in primarily to rescue poor families, single women, widows, and orphaned children from the danger of dissolute lives.”

Growth of Catholicism in the 20th Century

By the mid-20th century, Catholics had become assimilated into middle-class America. The third and fourth generational descendants of Catholic immigrants were no longer in the minority population and began to earn comparable incomes and level of education as the American Protestant. “They no longer needed–or wanted– to be protected from American society; they were part of it,” writes Wittberg.

During this time, government regulations began to impact the operations of hospitals, schools, and social service agencies, which shifted the institutions toward more secular practices. The children and grandchildren of the Catholic immigrants moved away from the inner cities and no longer needed the institutions that had been created for them. The inner-city Catholic ministries began to serve an increasingly diverse and increasingly non-Catholic population.

Prosperity Leads to Generous Support for Catholic Ministries

The movement and growth of the subsequent generations of Catholic immigrants also led to the establishment of the first Catholic foundations. Catholics who had experienced success in business endeavors chose to invest a portion of their earnings back into their communities, often as an expression of gratitude for the services provided by religious sisters, brothers and priests. Early partnerships were formed among Catholic lay business men and Catholic religious to assist with acquiring property and constructing facilities to expand hospitals, schools and other needed services.

Shifts in Religious Life after Vatican II

The influence of Vatican II elevated the importance of the laity as people sharing in God’s kingdom, and de-emphasized the religious hierarchy. This opened a pathway for increased participation of the laity in Church affairs, but also relegated non-ordained religious sisters and brothers to the status of laity. This led to a significant decline in the membership in religious orders, many of whom had staffed the Catholic hospitals, schools and social service agencies for decades. The financial strain of filling those positions with lay people as well as the challenge of maintaining Catholic identity in their absence have been pressing issues for Catholic organizations since that time.

In the years following Vatican II, many Catholic organizations transitioned away from direct ownership or sponsorship from a diocese or religious order. As Wittberg explained, a number of hospitals and educational institutions acquired recognition as a “Public Juridic Person” which is the “Catholic Canon Law equivalent of incorporation” and ensures the “Catholicity” of the institutions, while their civic nonprofit status is incorporated as a public charity under civil law. Although most of these institutions are no longer staffed by women and men from religious orders, many of them maintain Catholic sisters, brothers or priests on their boards to support their Catholic mission and provide the historical connection to the founding order.

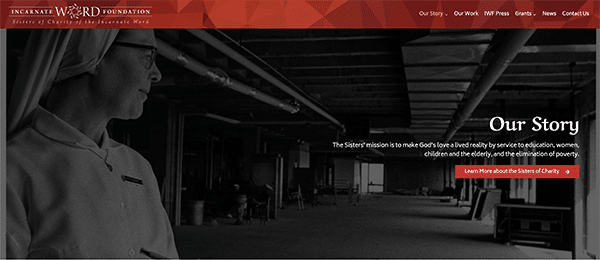

Religious Orders Become Grant-makers

As religious orders moved away from owning and sponsoring institutions, the proceeds from the transfers of property and assets were often utilized as an endowment to form grant-making organizations. A number of these organizations are commonly recognized as “healthcare conversion foundations” since they were formed from endowments created after the mergers or transferred ownership of hospitals. Many of these foundations may still be identified by the name of their founding hospital or founding order, such as the Good Samaritan Hospital Foundation, or the Sisters of Charity Foundation of Cleveland.

The Catholic Legacy in the 21st Century

Catholic organizations in the 21st century continue to face the concerns of the past: a further decline of membership in religious orders and ordained priests; decreased participation in parish life; and the pressures toward secularism from government regulations and societal demands.

As Catholic nonprofits face institutional challenges, the demand for their services continues to increase and signals the critical need for their survival. The National Council of Nonprofits revealed in their 2019 report that 23% of the 1.3 million charitable nonprofits in the U.S. were religiously affiliated organizations. One example of the impact of Catholic nonprofits is Catholic Charities USA, which is one of the largest social service agencies in the country, and serves 1 in 10 of all people experiencing poverty each year through its 3,000 affiliate agencies nationwide.

A significant challenge for Catholic fundraising is the prevailing assumption (even among Catholics) that all Catholic organizations are funded by the local Catholic diocese, or even the Catholic Church at large. Unfortunately, the reality that many Catholic organizations face is that the financial support from religious sponsors, including dioceses, parishes and religious orders continues to decline.

Finding Companions in the Field

–Henri Nouwen

Catholic foundations and funders are aware of the challenges of Catholic ministries, and often help to offset the financial strain from dissolved sponsorships from religious orders. However, foundations must mitigate their own challenges as their grant-making budgets are tied to endowments that rise and fall according to the global economy. For this reason, grant-makers are not always able to respond to financial needs at the level that is requested, or at the scale that they would prefer to respond.

Funders that support Catholic programs are as unique and diverse as the U.S. Catholic population. Some funders restrict their support exclusively to Catholic organizations, while other funders include Catholic organizations among their areas of support. Some funders may only support causes within their local diocese, while others support national and international causes.

Some of the benefits from working with a Catholic funder include:

- Most Catholic funders will support religiously-oriented programs that other foundations do not fund, such as programs within a parish or Catholic school, spiritual retreats, training for religious vocations, programs for or operated by religious orders, etc.

- Most Catholic funders understand and support Catholic social teaching and have at least basic level of understanding of the most pressing social issues.

Some unique dimensions of working with a Catholic funder may include:

- Some funders may limit funding to Catholic organizations specifically listed in the The Official Catholic Directory;

- Many Catholic funders have grant guidelines that require that funded programs do not violate fundamental Catholic Church tenets and align with Catholic social teaching;

- Some funders may support Catholic programs with the stipulation that people of other faiths are not denied services.

Navigating the Field with the Catholic Funding Guide

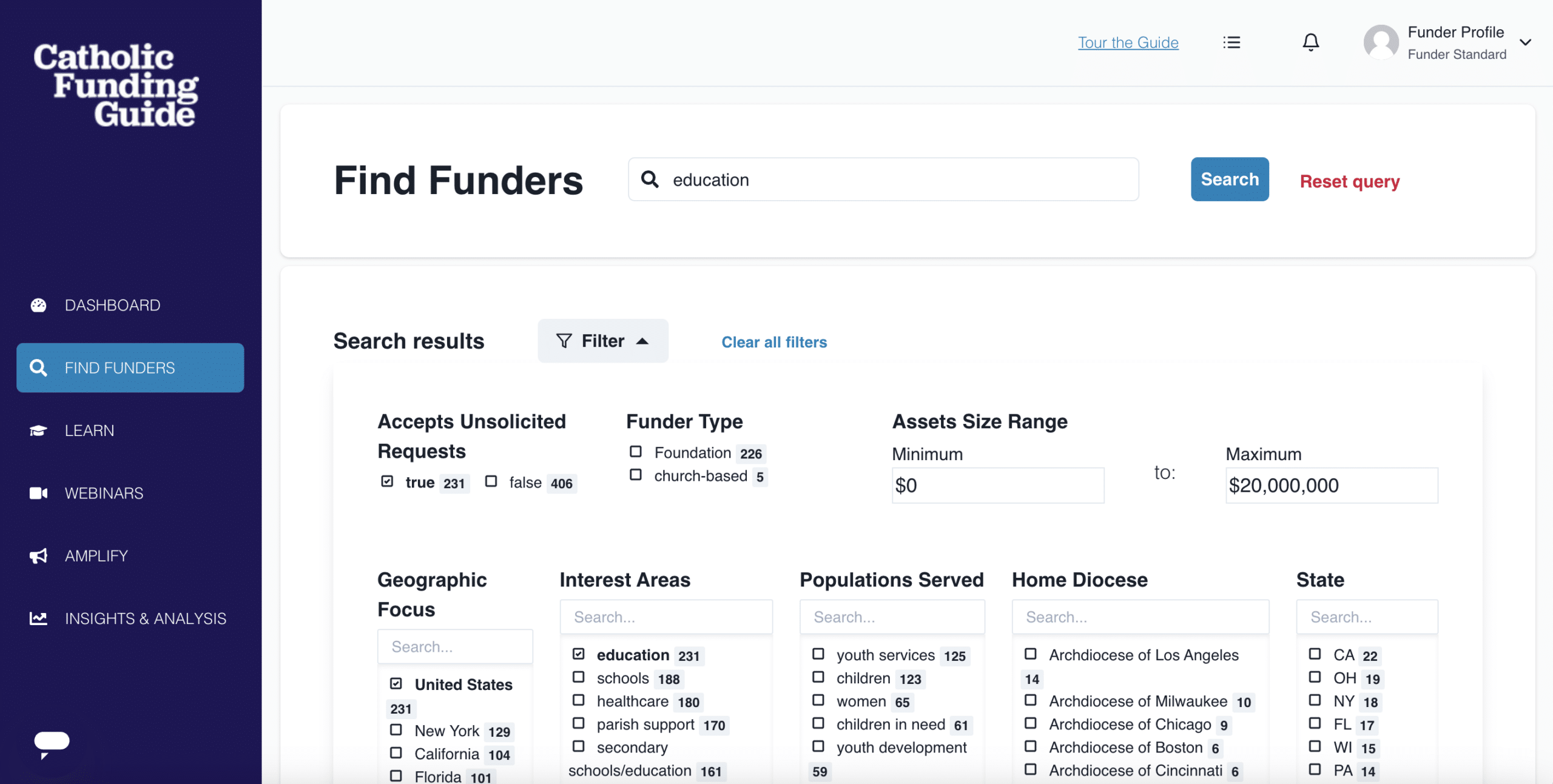

The Catholic Funding Guide serves as a trusted resource for Catholic organizations seeking grants, with a database of more than 2,000 funders who have demonstrated support for the Catholic Church, its ministries and social concerns. The funders listed in the Catholic Funding Guide are selected based on their previous support of Catholic ministries or programs, which may be a portion of their total grant-making, of the foundation’s entire grant portfolio.

Types of Funders

The Catholic Funding Guide provides access to:

1. Foundations –comprise about 93% of all funders listed in the Guide. The majority are independent (private), family foundations. Most independent and community foundations are required to report their charitable giving through the IRS Form 990-PF, which provides the public with helpful information regarding their funding focuses, application processes and methods for contacting the organization.

2. Church-based funders – often considered to be operating foundations since they are usually formed as a source of fundraising for their sponsored entity and may limit funding to a specific region or social issue. Examples would include a diocesan foundation created to support the diocese’s Catholic schools, or a national organization focusing on poverty or disaster relief. Since these organizations are typically considered ministries of the Catholic Church, they may not be required to follow the same IRS requirements as foundations, which may limit the amount of information available pertaining to their giving history.

3. Religious or fraternal organizations – charitable organizations established by a religious order, a Catholic membership society, or “conversion” foundations developed through Catholic healthcare systems. These organizations are also typically considered ministries of the Catholic Church and may not be required to publicly file reports on their charitable giving with the IRS.

–Henri Nouwen

4. International funding agencies – Although the primary focus of the Catholic Funding Guide is U.S.-based funders, the Guide does provide a list of agencies with an international funding scope. Awareness of these agencies may be helpful when considering support for ministries abroad or for understanding the Catholic church’s coordination of charitable work based in Rome.

One of the unique advantages for utilizing the Catholic Funding Guide is that the church-based, religious order, and/or fraternal organization funders are included in the Guide due to our relationship with the Catholic Church and Catholic philanthropists, and may not be found through other search engines.

Navigational Tools

The Catholic Funding Guide provides easy-to-use tools to help you identify prospective funding partners for your next project.

- Conducting a Search: One of the most important factors in establishing a funding partner is to ensure that the funder shares concern and interest for the same issues and causes that your Catholic nonprofit addresses. The Catholic Funding Guide provides search tools that allow you to identify funders based on focus area, population served, and geographic region.

Learn how to use Search tools in the Catholic Funding Guide - Survey the landscape: Review your list of prospective funders generated from the search process, and identify the prospects that most closely share your interests by reviewing the information on their Funder Profile page, including:

- A review of the funder’s grant history to determine if the prospective funder has previously supported programs similar to yours;

- A review the funder’s lists of staff and board members to determine if your organization has any connections that could assist with an introduction.

Learn more about the Funder Profiles in the Catholic Funding Guide.

- Determine the funder’s grant request process: The Catholic Funding Guide provides a convenient filter to help you sort prospective funders based on their utilization of an “open” or “closed” process for funding requests.

- Open process–By checking the “yes” box on the search filter “Accept Unsolicited Requests,” you can limit your search results to the funders with an open request process. If you are in need of funding in the next 12 to 24 months, this step will get you on track to collect more details for each funder’s application process. About 42% of all funders included in the Guide use an open process.An “open,” or “responsive” grant process for acquiring funding may involve several actions or inquiries through the duration of a grant request cycle. The first step is usually not a full grant application, but rather a “letter of intent or inquiry” (LOI) or a “pre-application.” Foundations determine their own timelines for grant cycles, which may be annual, semi-annual or quarterly, and will usually post this information on their website.

- Closed process– Choosing “no” within the same filter will provide you with the list of funders who use an invitation-only process. These funders tend to be highly focused on specific causes or community issues and usually welcome a letter of introduction from your organization if your services match their area of interest. The “donor cultivation” process may take longer with this type of funder but the effort may result in a stronger partnership.Foundations that utilize a “closed” or “invitation-only” grant process may operate annual, semi-annual or quarterly grant cycles, but will only promote the opportunity to apply to pre-selected organizations. The request process may include multiple steps, or may be simplified to a single application.

As your organization explores the types of grant processes employed by your funding prospects, some additional factors to consider are included in the tables below.

“Open” responsive grant process

Benefit

Nonprofits

This funding request process is appealing to organizations that do not have a previous relationship with the funder or newly established organizations.

Funders

An open process allows for the funder to identify new program needs and potential innovations.

Disadvantage

Nonprofits

The open process often attracts more applicants than can be funded by the foundation. The multi-stage application may require a significant investment of time with no guarantee of success. Responsive grant cycles may evolve over a period of six months to one year. Some grant awards may limit funding for one year. This often leads to a continuous application process for organizations that need multi-year funding.

Funders

This process often attracts more applicants than the foundation’s budget may support, so significant time is needed to review and select the applicants that most closely align with the funder’s grant making priorities.

Tips for nonprofits: Conduct your due diligence to verify your organization’s eligibility to request funding, and that your funding request aligns with the funder’s priorities. Research the types of grants the funder has supported in the past. Contact one of the funder’s previous grantees to ask for advice on the application process.

“Closed” or “invitation-only” grant process

Benefit

Nonprofits

Since the applicant pool has been narrowed, the chance of receiving a grant award may be more likely. Funders may also be more inclined to invest for a longer term of three to five years.

Funders

Funders conduct research to determine which organizations to include in the process and may limit the number of invitations based on their available grant budget.

Disadvantage

Nonprofits

A closed process may increase the difficulty for an organization to initially introduce itself to a foundation.

Funders

More internal research is needed for the pre-selection of applicants. Relying on the foundation’s research and its network for referrals may prohibit the foundation from discovering a truly innovative or extremely effective program.

Tips for nonprofits: When you have identified a funder with a history of supporting similar projects or causes to your own, pursue various options to introduce your organization and project to the funder. Options include a personal phone call or email directly to foundation staff, an introduction through another funder or grantee of the funder, or an introduction through a board member or another community partner.

As your organization considers the opportunities to cultivate a relationship with potential funders, it is advisable to consider your own capacity and availability when selecting the number of funders that you would like to cultivate. The best relationships require a significant investment of time and effort in order to enjoy the fruits of your labor.

Growing Authentic Relationships with Foundations

Once you have narrowed your list of prospects to determine the funders that most closely match your organization’s interests, it is important to build your understanding of the funder, their philosophy, and their funding strategies.

Grow in understanding. One of the first sources of information to thoroughly review is the funder’s website. In addition to reviewing the website for eligibility guidelines, funding limitations, and application schedules, the funder’s blog or news posts may provide insights into their activities and organizational culture. Many funders may provide the opportunity to join their newsletter mailing list or to follow them on social media so you can gain a deeper understanding of how the foundation relates to its stakeholders.

Consider the funder’s grant-making strategy. Most foundations have strategic goals established by their governing board. The strategic goals are supported by the funder’s grant-making activity, which is directly tied to an annual grant budget as determined by the percentage of assets that the foundation’s board has approved for spending from the foundation’s endowment.

By law, the IRS requires that all private, independent foundations designate a minimum of 5% of their assets for charitable giving each year. A foundation’s board may determine a higher percentage for the grant budget, especially if the foundation is responding to increased demands due to a natural disaster, economic crisis or other unique event. However, an economic crisis often impacts the stock market which impacts the foundation’s endowment. Many foundations base their grant budget off of a percentage of the three- or five-year average of their endowment to avoid huge shifts in their grant-making.

A funder’s budget may influence their decision to utilize an “open” or “closed” funding request process, or a combination of both options. However, foundations may also have practical or theoretical reasons for choosing their grant request process.

“…if you are trying to solve a big problem that affects a lot of people, this is probably not the kind of problem solved by an open process.”

“You have to ask, what are you trying to fix – or what problem are you trying to solve?” shared Specialty Family Foundation’s Joe Womac. “If generating ideas and innovation is the goal, then an open process works well. However, if you are trying to solve a big problem that affects a lot of people, this is probably not the kind of problem solved by an open process.” Womac shared that the Specialty Family Foundation is located in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which is home to the largest system of Catholic schools in the U.S., but also is faced with the highest level of poverty. “Over time, we have worked with about 100 schools that needed help and worked with them intentionally,” shared Womac. He noted that the foundation worked with a smaller number of targeted schools over a period of ten years. As the foundation continued to build their relationship with the schools, they also became more familiar with each school’s additional community partners. “We do not want to be ‘just a funder,’” stated Womac, “We want to be a partner and share risk.”

One of the foundations in the Catholic Funding Guide who utilizes an invitation-only process is the Catholic Community Foundation of Minnesota, which developed a “Grantseeker’s Guidebook” to help potential grantees gain a better understanding of the foundation’s mission, funding focus areas, and types of grants. Meg Payne Nelson shared, “Our application process is not open to everyone, but we are interested in hearing about opportunities for funding that may be a good match for our support.” Nelson recommends that organizations are very transparent about what they are interested in and should be “very specific about how they will meet the goals of the funder.”

The Specialty Family Foundation shares a similar approach. “A lot of grantees have built a relationship with us from a phone call,” shared Womac, who noted that he will give any organization that calls five minutes of his time, and then schedule a call for an additional 30-60 minutes if they have presented a compelling case. Womac shared that a year or two may pass after the initial conversation before he may be able to reconnect with the organization, saying, “I told you I wasn’t going to forget about you,” with an invitation for the organization to apply for a grant.

Both foundations utilize similar due diligence and research procedures to identify potential grantees. The Catholic Community Foundation utilizes its grants committee members who are well-connected with the community to identify prospective grantees. “Sometimes we will ask the staff at our local Catholic Charities office to suggest an organization that is effectively working on a specific issue, or we will ask other funders to provide referrals for organizations who have demonstrated great impact,” shared Nelson.

Womac adds, “Organizations need to do their homework before contacting us. Don’t try to convince a foundation to be interested in a different topic. You should only call the foundations who you really believe are investing in similar programs to your own.”

Some additional considerations for connecting with a funder include:

- Identify the community or subject area leaders. Some foundations choose to intentionally partner with organizations who are working comprehensively on a complex issue, which may involve longer-term support from the funder for multiple years. This allows for greater space and time for the partnership to grow between the grantor and the grantee, and for the program to deliver outcomes that can be measured and tracked over time. Ultimately, funders are more interested in the impact of the grantee’s services, and how those services are contributing to the common good and human flourishing.

- Discover the funders that promote education and training. Funders often offer community events to educate and/or advocate for specific issues. They may also sponsor capacity-building workshops to help nonprofits improve their operational or management skills or to increase board engagement. Many of these opportunities are open to any nonprofit organization and could provide a natural introduction to the funder or other community partners.

- Identify the effective communicators and community builders. Funders who want to be recognized as community builders often share stories that demonstrate the impact their investments have had with the community through the work of their grantees. Look for opportunities to share your story with the foundation through correspondence, blog posts, or newsletters, or by offering an invitation to tour your facility or attend one of your events.

“Foundations need to tell their story,” shared Womac. “We have a duty to the public to share the public benefit of our work – with more transparency than a 990 form. We want to make sure our program investments are working, and not causing harm.” To accomplish this, Specialty Family Foundation hires third party evaluators to measure the impact of their program investments, and then publishes the findings. “This transparency offsets the closed process,” added Womac. “We publish the wins and losses, and give credit where it is due.”

Tending the Harvest: Managing the Grant Award

The benefits, and the responsibilities, of your funder/grantee relationship do not end when a grant is awarded. As in all effective relationships, communication is vital. Here are a few tips to consider for successful grant management:

- Provide timely and appropriate acknowledgement of the grant award. Review the funder’s grant guidelines to determine how the funder prefers to be acknowledged. Some funders may wish to give anonymously while others expect or encourage public recognition.

- Adhere to grant guidelines for submitting progress reports and providing accountability to the foundation. Fulfill report requests on time with pertinent information. Accurate and timely reporting not only supports the effectiveness of your relationship with the funder, it may also be a factor in future funding decisions.

- Inform the foundation if any significant changes occur with your organization or the funded program, including changes to staffing, budget, timelines or anticipated results. Funders usually understand that many variables or unforeseen circumstances can prevent programs from progressing. However, most funders prefer to learn of the changes or challenges when they occur, rather than reading about a derailed initiative through a progress report or grant evaluation.

- If you work directly with the foundation’s program officer, develop a relationship with that person by checking in between reporting cycles to highlight any project milestones or good news whenever possible.

- If the foundation offers opportunities to highlight your program through their own publications or social media, consider sending photos and concise stories describing the impact of your program.

Contributing to the Kingdom of God

The impact of the thousands of Catholic ministries and institutions across the U.S. is vast and largely immeasurable. But the need for their services delivered with compassion and dignity for all is unquestionable. Our nation and world are in critical need of healing – the type of healing that may urge us toward a renewal of the pastoral care provided by our early 19th century ministries.

Catholic funders are also feeling urged to live their stewardship more deeply and look for innovative and collective approaches to meet increasing demands as well as address the root causes of societal issues.

The best way – and perhaps the only way – for Catholic ministries and Catholic funders to fully contribute to the kingdom of God is to come together in authentic relationships. Organizations should not let processes or misperceptions interfere with making a connection with a prospective funder. At the Catholic Community Foundation, “If your funding need aligns with the foundation’s mission, we are open to having a conversation,” shared Nelson.

Catholic funders prioritize mission advancement, and understand the risks involved in these types of partnerships. At the Specialty Family Foundation, “Our purpose is to help others, and make sure the heroes get the resources. We are not the heroes,” shared Womac.

In the midst of the daily work within a society that demands accountability, strategic plans and increased productivity as measures of success, it may be difficult to see how the work of Catholic philanthropy is different than in the secular world. Henri Nouwen reminds us that Christians approach this work through “spiritual communion” where those measures of success are “only by-products of a deeper creative energy, the energy of love planted and nurtured in the lives of people in and through our relationship with Jesus.”

The relationships cultivated by Catholic funders and ministries are intertwined and nourished by the love of Christ – the true vine, who reminds us:

“Just as a branch cannot bear fruit on its own unless it remains on the vine, so neither can you unless you remain in me.

I am the vine, you are the branches. Whoever remains in me and I in him will bear much fruit.” – John 15:4-5

Photo credits: ministry images from Sisters of Charity of Cincinnati, Saint Francis Health System and Catholic Charities of East Tennessee; vineyard images by Amelia Riedel.